Contents

Interest

Perhaps one of the most fundamental forces in art is interest. I mean this in the broadest sense, a force that causes attraction – or repulsion in the case of its negative – of an experiencer drawing and holding attention. In music, when interest happens, we find ourselves listening, or wanting to listen more deeply.

Art has its foundations on things that are interesting – ideas, the qualities of sounds, colours, shapes, i.e. materials that we find interesting are arranged in relationships we find interesting. Self-expression, “saying something”, beauty, profundity, or whatever are all well and good, and not that these don’t have value, but if it isn’t interesting, there’s little chance anyone, the artist included, is going to give it the time of day. These qualities also share the fact that they can be very interesting. Of course, that doesn’t mean that everything that’s interesting is art.

The significance of interest should be plainly obvious to most people, almost to the point of being taken for granted. As composers, we usually use materials that we find interesting, and that we think a listener would find interesting.

This, however, is limited to the end aesthetic experience. Before this, artists often have to work very hard in order to achieve a desired standard, especially where technique is concerned.

Practice

With regards to my own musical endeavours, this equates to composition exercises in harmony, counterpoint, instrumentation, orchestration, composing a lot of my own music, etc., all of which I have done diligently; and to guitar exercises and learning pieces.

You might have noticed I didn’t specify much about the guitar exercises.

Oops.

I confess, I haven’t been so diligent with all the exercises that guitarists are supposed to do, and my scales and arpeggios are almost embarrassing. I should probably clean up my act.

Boredom

The problem lies in the boredom. There are countless exercises, and while I’m sure they can all benefit me somehow, I just can’t be bothered half the time – they’re boring.

As easy as it is to conclude that this attitude is a character flaw and a sign of laziness, all of us as humans are subject to the forces of interest and boredom in pretty much every moment of our lives. I expect animals are too.

Interest, boredom and practising

Assuming that we decided that there really may be value in an activity we find boring, there are a couple of things we can do: we can bear down on our aversion to the activity and fight it, doing it and forcing our attention on the activity despite the boredom, or we can act more skilfully and learn to use them both to our advantage.

In a state of interest, attention is more focussed, and when attention is focussed, we’re more receptive to learning than when we’re bored, so cultivating interest is clearly beneficial. Plus, we have a right to demand more fulfilment enjoyment from each moment of the precious time we spend with a musical instrument.

Where is interest?

Where can we find this all-important interest? If I find one thing boring, but someone else finds it interesting, clearly the interest, and therefore also the boring, cannot be in the thing itself. It must be in me.

So yes, I lied – scales and arpeggios aren’t boring, I am.

Or at least the way I’ve looked at them is.

Perhaps it’s a preference for direct relevance to what I want to be able to play. I’m generally happier practising portions of a piece with careful precision, paying attention to hand positions, tone, etc., than practising scales and arpeggios arbitrarily. Maybe if I joined jam sessions in unexpected keys, I might end up practising them more. I should mention that I am satisfied with my knowledge of the fretboard and other theoretical aspects, which I have acquired through other means.

Interest and boredom arises in an experience with an object or an activity. While the precise workings of this are not quite clear to me yet – this is a weekly blog, not an academic paper – this week I have been looking at two determining factors that are important for practice: the perceived sense of newness and progress.

If it is new, especially if it seems to promise something pleasurable, it draws interest. By observing further, we find more things, more new things, and interest develops, attention is held. If we finding something else interesting in the same object, we naturally explore it further, until the interest subsides, or something more interesting distracts us.

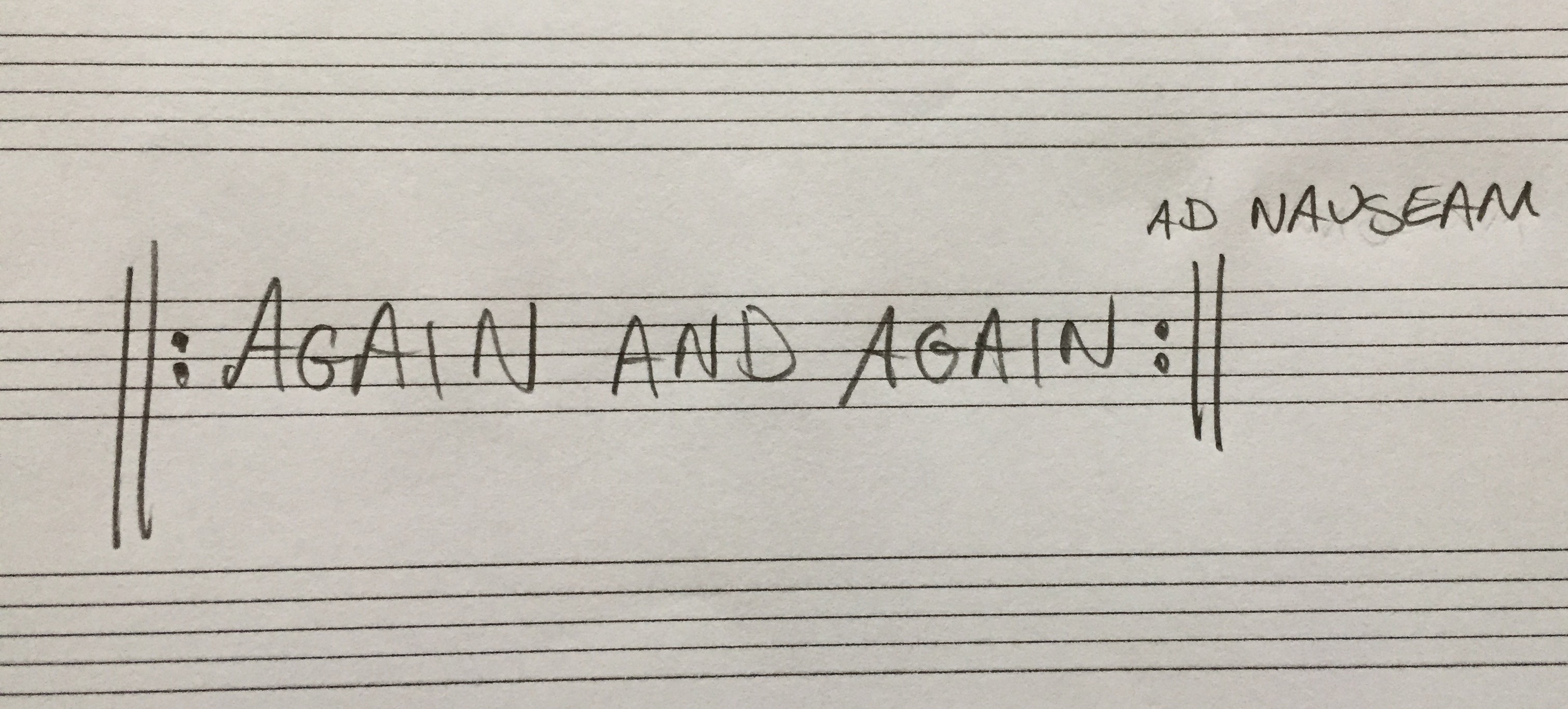

Repetition

Repetition, as with probably every skill, is an inescapable part of learning something. This is really what practice of any kind boils down to. You do lots of the good stuff again and again, the stuff you want to be able to do, making sure you don’t do any of the bad stuff, and that’s it. All good habits, and no bad habits. Hopefully.

The fact that repetition is necessary is good, because if we learnt a new behaviours in single occurrences, we’d probably have all of our appropriately adapted behaviours changing constantly and unlearnt. I’m guessing, however, that we actually do learn and unlearn behaviours at every moment, and that repetitive practice deals with the sum total of very large numbers of learned behaviours.

Problems with repetition

When we learn a piece of music we repeat what we want to be able to do to develop the degree of security necessary to play it convincingly. The problem I often find with repetition is that with the variable level of interest, which tends towards slight boredom, my attention starts to fade when I practise something specific.

Once I’ve managed to establish the precise hand movements necessary in a small portion of a piece and can do them at a given speed, I repeat the portion to consolidate it. Playing it 5 times, I might find that a lapse in attention, either on the music or on the hand movements, leads to a mistake. We don’t want any mistakes, because they lead to a lack of security.

Using effort to focus, I might play it 10 times or so satisfactorily. As pleased as I might be that I can play the passage with greater security, the levels of boredom would generally rise, perhaps just slightly, but enough to create a certain degree of subtle repulsion, and I might still have to come back to it again and again.

I don’t believe there needs to be any repulsion in practice. Indeed, we all go through hardships to achieve what we want, but that doesn’t mean that our daily practice cannot be fulfilling in every moment. I believe the key is to manage the forces of interest and boredom skilfully.

Experimental music memorisation technique

I’ve been experimenting with a way of learning a piece of music that involves shifting focus from passage to passage. I’ve been noticing how attention can often benefit from being “refreshed”, by that I mean that between repetitions, or groups of repetitions, I pause, maybe take a breath or very briefly look out the window, and then return to practising. In the same way, after practising one passage over and over again and I get to the point where I’ve had enough, I find working on a different part of the piece can be refreshing too. This gave me an idea of how to do this more efficiently.

Pimsleur’s space-repetition

I’ve used the Pimsleur series to learn a few different languages. These are very structured audio language courses, which include something called “spaced-repetition system“, or more specifically “gradual interval recall”, in which the learner is asked to recall vocabulary and grammatical elements of the language at gradually larger time intervals. For example, Pimsleur reviews new language after intervals of 5 seconds, 25 seconds, 2 minutes, 10 minutes, 1 hour, 5 hours, 1 day, 5 days, 25 days, and so on. It will also teach or review other language within those intervals in the same way, so the process is all the more efficient.

I found these courses really effective. So why not use this for learning a piece of music? What I’ve been doing is practising a passage by playing a few repetitions of it carefully at a speed I can play it perfectly, until I get a slight feeling that it’s too much and repeating further will lead to confusion rather than security. Then I do the same with another passage. Then I go back to the previous passage, all the while assessing what needs to be worked on, how, slower/faster, etc., repeating as much as attention allows. Then I return to the other bit and practise it, then some other passage, and I continue the process as long as I want. Varying the passages maintains interest and prevents boredom. I should stress that effort to focus attention is necessary and beneficial at every moment, and also the ability to focus improves through this effort.

I actually I started doing this naturally by playing a passage, then getting bored or fed up, and then getting distracted by noticing another bit that I needed to work on, and then remembering that I had intended to be practise the bit I had got distracted from. You can see how the two forces of interest and boredom are at work here. One way to deal with being pushed about by these forces might be simply to use more effort to focus, but perhaps like this they can also be used skilfully.

So the aim is to keep interest high, and therefore attention focussed. Boredom, on the other hand can be noticed and used as an indicator of when the necessary interest is lacking, so that you can:

- Increase effort to focus attention

- Look more carefully at one curious aspect of the passage and practise it

- Change the way you’re practising the passage, tempo,

- Focus on a specific aspect, e.g. the physical sensations of one hand, the movements you can see, the sound, the movement of the music (see also Playful and experimental practice from last week)

- Practise a different passage.

I expect there are a multitude of different ways to work with interest and boredom skilfully that I have yet to discover. We’ll let time tell how all this manifests in my playing!