As part of my efforts to develop my writing for the guitar, I’ve begun a new composition project to explore a particular area. It’s nothing new on the guitar or in music, but it’s one of my favourite things, and something that I take great delight, as well as pains, in playing and composing. This is counterpoint.

In this week’s post I’ll tell you about this project. I’ll discuss counterpoint and what it is briefly, the difficulties the guitar has with it, and finally the score of the first composition.

Counterpoint indeed.

I like counterpoint.

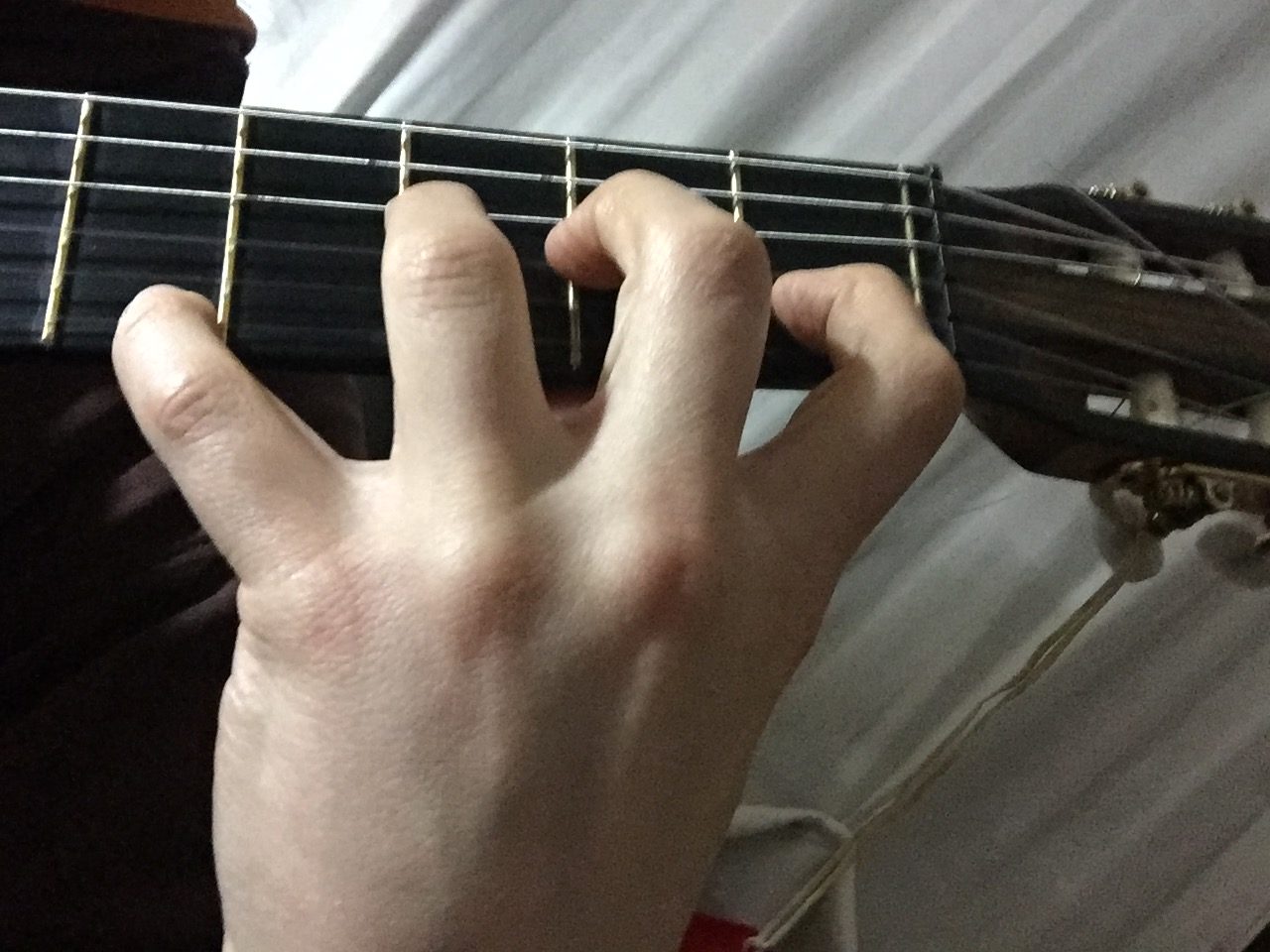

As well as liking it, I want to be able to write contrapuntal music that feels natural on the hands and doesn’t make the left hand look and feel like it’s playing Twister at breakneck speed.

Contrapuntal composition is already something rather complex, since the strict rules in some styles often mean you’re left with very few notes to choose from, and then with the further limitations of the guitar, you can be left with no music at all.

So I’ll begin with a short discussion on what it’s like playing and writing it on the guitar, and then show you the score of first step in this project.

What is it?

If you don’t know what counterpoint is, it means music with several different melodies played at once, often with strict rules governing how they intertwine with one another. “Contrapuntal” music is also sometimes called “polyphony”, many (i.e. at least two) voices singing together, perceptible independently and as one. As well as voices, contrapuntal music works with several instruments playing together, or with one like the piano that can play several notes at once. It’s also supposed to work on the guitar…

I won’t bore you with any more explanations or with why I like it, because it’s better if you experience it, and I very much hope you get the chance to do so.

Composing and playing

Where it gets tricky

The guitar with its six strings – you’d expect it to be quite suitable for counterpoint, wouldn’t you? Well, yes, but we do only use four fingers on each hand. Still, that should be enough, shouldn’t it? Yes, but you generally use one finger from each hand per note, and when one note follows another, you generally want to use a different finger, just like you prefer to use the other foot for your next step when you’re out for a walk, otherwise you’d be out for a hop. So four divided by two leaves us with enough fingers to more or less comfortably manage two melodic lines. Two-voice counterpoint is all well and good, but it never really gets interesting unless there are at least three voices; we’re two fingers short of a fugue. Poor guitar, poor guitarists.

But wait, there’s more to the guitar than that – guitarists can also play on open strings, use all manner of barrés, play several notes with the thumb etc. etc., so maybe there is hope?

Yes, it certainly is possible, but the composer and guitarist are practically handcuffed in the limitations we constantly work under. To illustrate it rather bluntly: the guitar, with its wonderful palette of timbres, has been described as an orchestra in miniature. This is true, but in this orchestra it’s like the entire string section gets their left arms hacked off temporarily whenever there’s a clarinet solo.

The rules of counterpoint are severe enough already, surely any more limitations will just be suicide? Well, it seems we end up having to find a way to use just the string players’ right hands, or carefully and musically craft the amputation so audience doesn’t notice.

Apologies for the graphic analogy, but hopefully you might know what I mean. They do get their arms back in the end.

The project

Canons

One of the projects I’ve been thinking about that I mentioned last week is a series of canons. The other piece from the last few weeks will make a return at some point (along with the other movements), but once it’s more polished and I can play it all for you.

To begin with, I’ve decided to write a series of canons for the guitar that I can actually play. I’m going to write different canons for different numbers of voices. Just for some numerical fun and to force me to be creative with my solutions to problems, I’m planning to write 2 canons for 2 voices, 3 for 3 voices and so on up to 6 canons for 6 voices – the number of strings on the guitar. The 6 are probably borderline impossible, but the challenge will be interesting.

First attempt – Canon for Six Voices at the Fourth

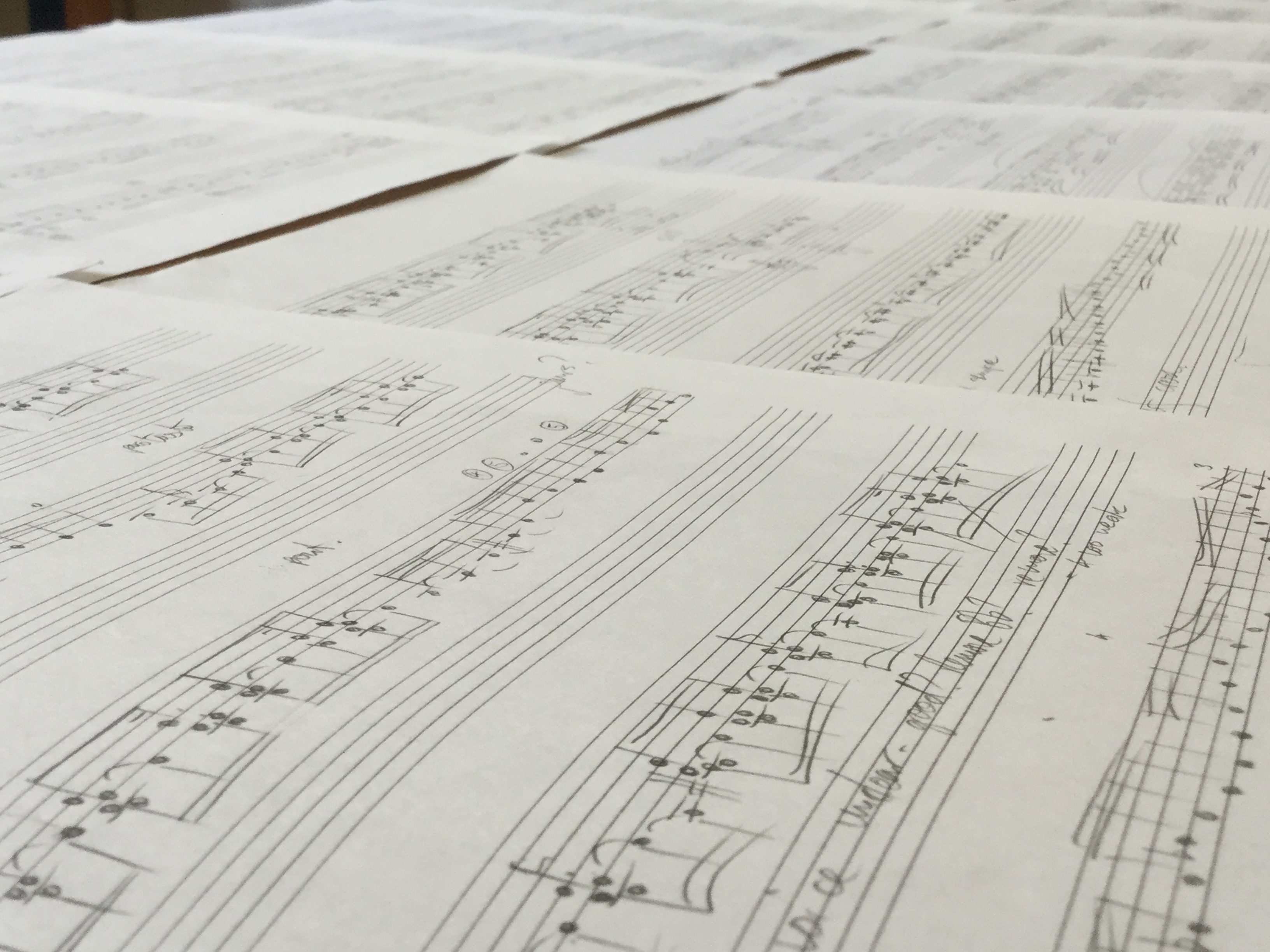

Click here for the score of the first canon.

With six voices on six strings, I jumped in at the deep end, but it was the most interesting-sounding challenge. I used a few tricks to keep things as simple as possible.

Some points about how I wrote it:

- I’ve written it on two staves to facilitate visibility. I hope you can read bass clef.

- To simplify the technical side a little, I designed it so that each voice occupies its own string.

- It’s a canon at the fourth, i.e. each voice enters at an interval of a perfect fourth above the previous entry. This makes use of the guitar’s tuning – the strings are a perfect fourth apart, except the highest two. To maintain musical rigour, the six entries all begin a fourth apart, rather than simply on the first note of each string, which does make it more difficult to play.

- The melody is sombre and very simple, and each voice remains within the range of a major third, i.e. one less than the aforementioned perfect fourth, in order to avoid crossing voices and the technical complications that this entails. The guidelines of counterpoint indicate that melodic lines should span at least a sixth for the sake of interest, so a third could end up being boring. There are, however, two semitones in the melody, which I think gives it an interesting tension.

- The harmony is relatively free, and to my mind sounds like Gesualdo at times. There are things like suspensions, but not resolved according to the traditional rules. I pretty much just went with whatever was available on the fretboard and sounded interesting and acceptable to my ear, which I think has developed into it’s own characteristic sonority.

- There aren’t really many jumps from one difficult chord shape to another, and voices often move by fingers just sliding up and down the strings.

- There are some pretty diabolical stretches in the left hand, specifically bars 5 and 6; perhaps I should warn you that my hands aren’t all that small, but my left hand is really at its limits here. There is the possibility of tuning strings 1 and 2 up a semitone to C and F respectively, but that is not without it’s complications in other places too.

There. A first short and almost simple canon. I did want and try to make it go up in fourths continually so that it goes round the circle of fifths and all twelve tones and then starts again at the first E, but that turned out a bit too tricky for me right now. Maybe next time.

Next week’s post

Next week I’ll play it for you. Watch this space!

Comments and questions

I’d be very interested to hear about any of your thoughts about composing or playing contrapuntal music on the guitar, and of course any comments or questions you might have on the subject.

Let me know if you have a go at playing the canon too!